Disney World's biogas facility: a model for converting food waste into energy

As the US generates 35m tons of food waste yearly, biodigesters could be big business. Harvest Power hopes to crack the code

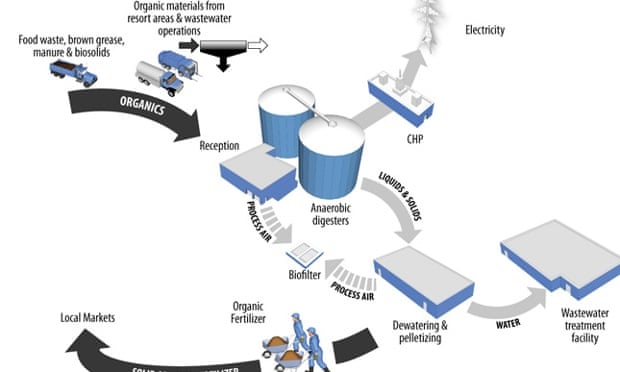

Governments and companies alike are interested in digesters that turn food waste and biosolids into biogas, like this Harvest Power system. Photo: Harvest Power

Millions of people a year visit Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, the world’s most popular theme park. These days, some of the food that they don’t eat – as well as some of the food they do – ends up being used to make electricity for the resort’s theme parks and hotels.

How? Food waste – including table scraps, used cooking oils and grease – is collected from selected restaurants in the Disney World complex, as well as area hotels and food processors, and sent to a system of giant tanks at a facility near the park. There, the food waste is mixed with biosolids – the nutrient-rich organic materials left over after sewage is treated – and fed to microorganisms that produce biogas, a mix of methane and carbon dioxide. The biogas is combusted in generators to make electricity, and the remaining solids can be processed into fertilizer.

The circular economy at Disney World may not be as pretty as Cinderella’s Castle, but this process for turning organic waste into energy, which is known asanaerobic digestion, could turn out to be the best way to extract value from food scraps and treated sewage that would otherwise wind up in a landfill.

“We’re able to turn all of the waste stream into productive products,” saysKathleen Ligocki, the chief executive of Harvest Power, a venture capital-funded clean-tech company that built the Florida facility. “This is our goal – pumpkins to power, waste to wealth.”

Harvest Power operates anaerobic digesters in Vancouver, British Columbia, and London, Ontario, as well as this one, near Orlando. Photograph: Harvest Power

Founded in 2008, Harvest Power is headquartered in Waltham, Masachusetts, and operates in New England, California and the Carolinas, as well as Florida. The company operates anaerobic digesters in Vancouver, British Columbia, and London, Ontario, as well as the one near Orlando. Elsewhere it recycles organic matter the old-fashioned way, by composting. Harvest Power has been named to the Global Cleantech 100, a list of the top private clean tech companies, for five years in a row.

Last week, Ligocki, who was installed as CEO in January, spoke at the unveiling of the Cleantech 100 list in Washington. She was bracingly honest about Harvest Power’s strengths and weaknesses, comparing the company to a teenage boy – “gangly, awkward, big and not quite organized” – that needs to mature into a well-functioning adult. The company has raised $225m in equity from funds including including Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB) and Generation Investment Management, along with $100m in debt. While it will generate about $150m in revenues this year, it is not yet profitable.

It’s going after a big market: in 2012, according to EPA, more than 35m tons of food waste was generated, with only 5% diverted from landfills and incinerators. Most of that is composted – accurate and timely data is hard to come by – but local governments and companies are increasingly interested in digesters that turn food waste and biosolids into biogas. A Gold River, California-based company called Clean Worlddesigned and built a biodigester for the city of Sacramento that turns about 100 tons of food waste per day into natural gas, electricity and fertilizer. Neo Energy is developing several anaerobic digestion projects in Massachusetts, which now requires colleges, hospitals, hotels and supermarkets to recycle food waste. In Europe, meanwhile, anaerobic digesters are widespread, with more 9,000 of the plants in Germany alone, most of them small-scale and devoted to recycling farm waste.

The economics of biogas digesters in the US are promising, Harvest Power’s Ligocki told me the other day by phone. The company relies on three revenue streams: one set of customers pays Harvest Power to take waste. Another, typically the local utility, buys its electricity. And its fertilizers are used in agriculture, horticulture, professional turf, and retail lawn and garden applications; the company’s biggest retail distributor is Lowe’s.

Not surprisingly, Harvest Power’s business model works best on the east and west coasts of the US, where landfill capacity is tight and thus tipping fees are high, and where electricity prices tend to be higher than in the middle of the country, which burns a lot of low-cost but dirty coal. The trick is to generate enough revenue to repay the capital investment in a large-scale facility – the one at Disney World cost about $30m to build, Ligocki says.

“The Florida operation is profitable, and as we build the fertilizer business, it will be more profitable,” she said. The plant will process about 120,000 tons of organic material per year and produce 5.4 megawatts of combined heat and electricity, which is enough to fuel 2,000 Florida homes. That meets only a fraction of the energy needs of Disney World, which has more than 30,000 hotel rooms.

Scaling Harvest Power is at the top of Ligocki’s to-do list. Other cities are potential customers, but she notes that “municipalities are, by their nature, a little bit conservative, as they should be since they are using taxpayer dollars.” Another option is to work with garbage companies who want to extract value from the waste they now dump. “Many of the haulers – the Waste Managements and the Republics of the world who run landfills – know this is happening, and so we are going to collaborate with them,” she said.

Ligocki came to Harvest Power after a stint as a partner at Kleiner Perkins. She previously led Next Autoworks, an auto start-up backed by Kleiner Perkins and Google Ventures, and before worked at General Motors, Ford, United Technologies and auto suppliers, traveling to about 180 countries. For her, this assignment is personal.

“I’ve traveled a lot around the world, and I understand that we are very fortunate to live in a wealthy, industrialized country,” she told me. “But when wealth goes up, waste goes up as well.” If Harvest Power and its rivals succeed, at a scale that matters, food waste, at least, will no longer go to waste.