Garbage in, graphite and green hydrogen out

Natural graphite, a high grade of coal, is 1 of 20 raw materials that the EU has identified as critical to its economy and for which it is largely dependent on imports. A reliable source of synthetic graphite could help secure Europe’s supply and green hydrogen would help to minimise the environmental footprint of many promising applications. In this regard, mixed food waste can be used as a feedstock to manufacture products for two significant growing markets: high value graphitic carbon and renewable hydrogen (RH2).

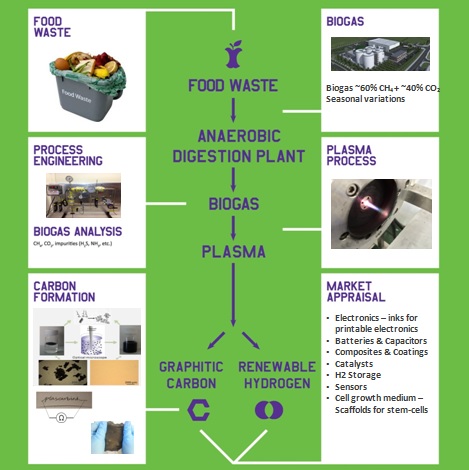

Process Flow Diagram, Source project plascarb

Plascarb: Transforming food waste into treasure

The project PlasCarb aims to use innovative technology to produce graphitic carbon and renewable hydrogen from food waste, – EU identified critical and valuable products. “The objective of PlasCarb is twofold,” says project coordinator Neville Slack from the Centre for Process Innovation in the UK. “One objective is to see how we could utilise food waste instead of sending it to landfill or just putting it through an anaerobic digester to generate electricity. The second is looking at potentially critical outputs”, synthetic graphite and green hydrogen.

Combining anaerobic digestion with an innovative microwave plasma technology

The partners plan to develop a plant that will integrate the whole process, from the production of biogas to the isolation and purification of graphitic carbon and green hydrogen. The biogas generated from food waste is broken down in an anaerobic digester. The aim is then to split this gas into its two main components — methane and carbon dioxide — using a filtration and cleaning process developed by the project. The biomethane (CH4), once isolated is injected into the plasma reactor, where it is heated using low-energy microwave technology until the molecules come apart, forming graphitic carbon (C) and hydrogen (H2).

Challenges

One of the challenges lies in ensuring that the process delivers carbon in the desired form. Another arises from the complexity of separating the two substances. Further steps are required to divide the two and eliminate impurities. By the time the project ends in November 2016, the partners hope to operate the plant for at least one month, processing over 150 tonnes of food waste into more than 25 000 cubic metres of biogas.

For more details visit, www.plascarb.eu

Text by : Neville Slack,Coordinator of PlasCarb Project